Student Stories: The Green Transition and Aguachile in Hermosillo, Mexico

Bryan Tam is a second-year MPA/ID student at Harvard Kennedy School. Bryan was accepted into our Summer Internship program and contributed to our ongoing project examining productive diversification in Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico.

Why did you apply to the Growth Lab Summer Internship?

I applied to the Growth Lab Summer Internship because I was drawn to the idea of working on economic development projects in a cultural and political context different from what I was familiar with. Through its project in Hermosillo (Mexico), the Growth Lab provided me with that opportunity. Coming from Malaysia, Latin America is halfway around the world and was not a cultural or political context that I frequently encountered. The topic of potential economic opportunities arising from recent trends in nearshoring and the green transition held significant interest for me as well.

What did you work on?

I worked on a diagnostic assessment to evaluate the viability of several potential economic opportunities emerging from recent trends in nearshoring and the green transition, including solar panel manufacturing, EV battery manufacturing, and semiconductor manufacturing. This involved understanding the prerequisites for a region to be competitive in these industries and assessing whether these prerequisites were present or likely to be present in Sonora.

In what ways were you challenged?

Unsurprisingly, the language barrier was one of my biggest challenges while in Mexico. The primary language in Mexico is Spanish, and having had no prior knowledge of the language, it took me time to learn some basic Spanish and conduct research on information sources, which were primarily in Spanish. I remember how reliant I was on sign language and Google Translate on my first night in Mexico—many frantic gestures and Duolingo lessons later, I am happy to say that I can navigate a restaurant and order food in Spanish (well, sort of, assuming the waiter speaks slowly and doesn’t use too many words I haven’t learned on Duolingo).

What was your most exciting/surprising experience?

My most surprising experience was discovering how friendly and hospitable Mexicans are! A special shoutout goes to my client counterpart, Fernando, who went out of his way to show me around Sonora and introduce me to his family. He truly made me feel welcome in a very foreign country and gave me a lot of advice as I traveled around Mexico. This is not to forget everyone else who also displayed the incredible hospitality that I now associate with Mexico—Manuel, Alejandro, Nitzia, and many others that I have met. Their warmth and kindness really made me appreciate Mexico so much more and enriched my overall experience.

What advice would you give to future interns?

My advice is to be open to exploring new places and having new experiences. The foreign geographies that Growth Lab interns are usually placed into hold so many cultural experiences for those not accustomed to them. Speaking from my own experience, I am very happy that I took the plunge and explored a place very different from what I was used to. Otherwise, I would never have experienced the incredible hospitality that a different culture could show me, tasted the delicious tacos and other foods (e.g., aguachile) that Mexico had to offer, or seen its breathtaking sights and sceneries.

What’s next for you?

I am still figuring out what’s next for me, but right now, I am focused on how to spend my second year well. It will be my final year at the Harvard Kennedy School, and inspired by my time in Mexico; I want to make it as fun and meaningful as possible. My experiences in Mexico have made me more open to stepping outside my comfort zone, and I may do so in my second year.

Student Stories: Morocco’s Female Labor Force and Cultural Delicacies

Anjali Nair is a second-year MPA/ID student at Harvard Kennedy School. She was accepted into the Growth Lab’s 2024 Summer Internship Program and contributed to the ongoing project in Morocco.

Why did you apply to the Growth Lab Summer Internship?

I wanted to deepen my understanding of growth diagnostics in practice, and this internship seemed like the perfect opportunity to do so. The Growth Lab team is known for asking insightful questions, formulating hypotheses, and building models to uncover each region’s binding constraint. Additionally, I’m particularly passionate about work at the intersection of gender and development. The chance to research Morocco’s low female labor force participation with the team and spend 10 weeks in Rabat was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up.

What did you work on?

My project centered on identifying the factors behind Morocco’s low female labor force participation. I started by reviewing existing research and consulting with experts at UM6P, the local university, and attending regional employment seminars. However, the most critical insights came from conducting qualitative interviews with women across Morocco. These conversations revealed that caretaking responsibilities and the scarcity of quality job opportunities were driving many women out of the labor force, and some even into the informal sector. Hence, to complement the team’s analysis of micro-risks, I delved into Moroccan labor regulations, focusing on those related to informality and gender-specific laws. In the final two weeks, I shifted my focus to firm-level data, where I analyzed wage and hiring trends across various industries and regions, which also helped me hone my coding skills.

In what ways were you challenged?

Two challenges stood out. First, grasping Morocco’s cultural context was crucial, especially when tackling complex issues like female labor force participation. It was important to distinguish whether women were choosing not to work out of personal preference or if they were constrained by family expectations, limited connections, or poor job quality. The qualitative interviews were essential in bridging the gap between existing reports and the lived experiences of Moroccan women. The second challenge was the scarcity of accessible official data. Initially, this seemed like a significant hurdle, but by partnering with local experts and students, we discovered alternative data sources, conducted our own interviews, and pieced together government reports to form a coherent narrative.

What was your most exciting/surprising experience?

The highlight of my experience was the extraordinary warmth of Moroccan hospitality. During our qualitative interviews, a UM6P student invited us to meet her extended family. What we anticipated as brief interviews around female labor force participation evolved into a memorable cultural exchange. Each home welcomed us with a spread of Moroccan delicacies—msemen, harcha, batbout, baghrir, and a willingness to share their experience with us. We were even invited to stay overnight, and the next afternoon, the matriarch even prepared couscous—a dish typically reserved for Friday family gatherings. I was especially touched when they went out of their way to make a vegetable couscous for me, knowing I didn’t eat meat. Additionally, learning to make baghrir from scratch, traditional fluffy pancakes best enjoyed with mint tea, is a memory I’ll always cherish. This experience truly embodied the essence of Moroccan kindness.

What advice would you give to future interns?

Come prepared to take initiative. Many focus areas at the Growth Lab are self-directed, so it’s crucial to set your own schedule and seek help when needed. Additionally, one of the most rewarding aspects of the internship is building connections with locals. I strongly recommend immersing yourself in a local community, whether in Morocco or another country. I started in a university dorm but quickly moved to the city, which enabled me to form deeper friendships and fully experience life in the country.

What’s next for you?

I’m entering my final year in the Master’s in Public Administration in International Development program. Building on my passion for gender-focused research and data analysis, I plan to focus on elective courses that deepen my expertise in these areas. Additionally, I’m excited to be back leading the next Women in Power Conference, where I’ll be dedicating time to organize discussions around gender equity and leadership.

Student Stories: Developing Global Metrics to Understand Country-Level Openness to Migration

Zahra Asghar is a second-year JD/MPP student at the Harvard Kennedy and Harvard Law Schools. She was accepted into the Growth Lab’s 2024 Summer Internship Program and contributed to the ongoing Migration project funded by the Templeton World Charity Foundation – an initiative aimed at developing de facto measures of country-level openness to migration and understanding which countries are most effective at integrating migrants.

Why did you apply to the Growth Lab Summer Internship?

I have been working on the ground in refugee resettlement and migrant support in some capacity since I was fifteen. Over the last decade, I have seen migration advocates increasingly begin making economic arguments in favor of migration, as opposed to the moral or political arguments that were effective in the past. This project would allow me the opportunity to understand the research underlying these arguments in more detail – what impacts have already been proven in the research, what gaps remain, and how such research is communicated to drive impact. While getting this exposure, I would also get the opportunity to work with a team on the cutting edge of answering the most critical questions on the topic!

What did you work on?

There are two primary areas the team is focused on – developing a de facto measure of openness to migration (as opposed to a de jure measure, such as a consolidated database of visa restrictions) and understanding which countries were most effective at integrating migrants. By May, when I began my work with the project, the openness measures had already been developed, so I focused on identifying potential use cases for the research and presentation materials for validation discussions with NGOs and other researchers. In terms of the economic integration question, I focused on consolidating and validating the initial cross-country dataset that will be used for analysis in the fall. I also began an initial literature review on the ways in which immigration can drive economic complexity and exports, to prepare for potential future questions the team might ask.

In what ways were you challenged?

As someone not coming from an academic research background, I spent much of the first weeks of the research project reading through the relevant literature and working to understand the methodology of the work. Thankfully, the team was immensely patient and ensured I got up to speed relatively quickly. Later in my experience, when it came to developing the integration database, many of the research databases we were pulling from were in languages that I had little to no fluency in, testing my ability to work in a foreign data environment and my ingenuity with Google translate.

What about this research most excites you?

I think this research has the potential to help a number of different types of stakeholders – countries, non-profit organizations, multilaterals, and academics – better understand the ‘softer’ levers that can influence immigration beyond visa restrictions or economic incentives. For countries with aging populations, increasing immigration is one lever they can use to stabilize their economies and drive growth, and understanding these types of factors can help inform best practices for attracting new immigrant populations and ensuring they are effectively integrated into their new communities.

What advice would you give to future interns?

Take advantage of your time at the Growth Lab! The teams are really invested in student growth, and the Lab is a fantastic place to learn. If you have a research question you are particularly interested in related to the project you are working on, you should share it with your team and carve out time to work on it while you have access to all the expertise they – and the broader Growth Lab Team – offer!

What’s next for you?

I have three years remaining of my joint policy and law degree. Over the next few years, I hope to work in public interest spaces around civil rights, including migrant rights and international human rights. This research experience has given me an important fluency in statistical research and migration literature that will greatly inform those experiences and make me more effective in driving impact.

Student Stories: Exploring Sovereign Wealth Funds and the Architecture of Baku

Abdullah Helal is a second-year student at Harvard Kennedy School. As part of the Growth Lab’s 2024 Summer Internship Program, he contributed to the project in Azerbaijan. The project focuses on advancing research and evidence-based policy development to address the challenges of economic diversification and job creation in a country transitioning from oil dependency.

Why did you apply to be a Growth Lab intern?

I applied for the Growth Lab internship because I wanted to gain firsthand experience working in an applied research think-tank that tackles the critical economic challenges facing countries today. The Growth Lab’s rigorous approach to economic analysis, which goes beyond traditional management consulting, deeply resonated with me. I valued the opportunity to contribute to impactful research while honing my skills in a setting that prioritizes evidence-based solutions.

What did you work on this summer?

This summer, I conducted a comparative analysis of sovereign wealth funds and their role in economic development, with a particular focus on the State Oil Fund of the Republic of Azerbaijan (SOFAZ). My research evaluated how SOFAZ and other sovereign wealth funds allocate their assets to balance economic development goals with their savings and stabilization mandates.

In what ways were you challenged?

I was challenged to move beyond merely descriptive research to a more analytical approach. My supervisor (shout-out to Felicia Belostecinic) set high expectations for not just the depth of analysis but also for how it was framed within a coherent and compelling narrative. The research needed to be both rigorous and practically applicable, contributing meaningfully to the overall project and addressing real economic challenges. I appreciated this push, as it helped me grow and ensured that my work was impactful.

What was your most exciting experience?

My most exciting experience was visiting Baku and immersing myself in its rich beauty, culture, and cuisine. As I roamed the city, I spent considerable time learning about its political and economic history, feeling as though I was truly discovering a new corner of the world. The city’s architecture was a visual delight, ranging from the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Old City of Baku to the futuristic Zaha Hadid–designed Heydar Aliyev Center.

What advice would you give future Growth Lab interns?

My advice to future Growth Lab interns is to be proactive. The experience is largely self-guided, but you’ll have all the support you need from the Growth Lab team. The more prepared you are with a clear research topic, the more effectively you’ll be able to use your time during the internship.

What’s next for you?

I’m returning to the Kennedy School to begin my second year in the MPA/ID program. I’ll be focusing on my Second Year Policy Analysis (SYPA) paper, and I believe my experience at the Growth Lab has given me a solid understanding of the research process, which will be invaluable as I work closely with my academic advisor.

The Myth of the Wyoming Migration Boomerang

By Eric Protzer

There is a popular concept in Wyoming known as the “boomerang” effect, which posits that people leave the state at high rates but often return later in life. This phenomenon is purported to support the long-term economic vitality of the state, as young people acquire experience elsewhere then move back to Wyoming with the skills they have acquired.

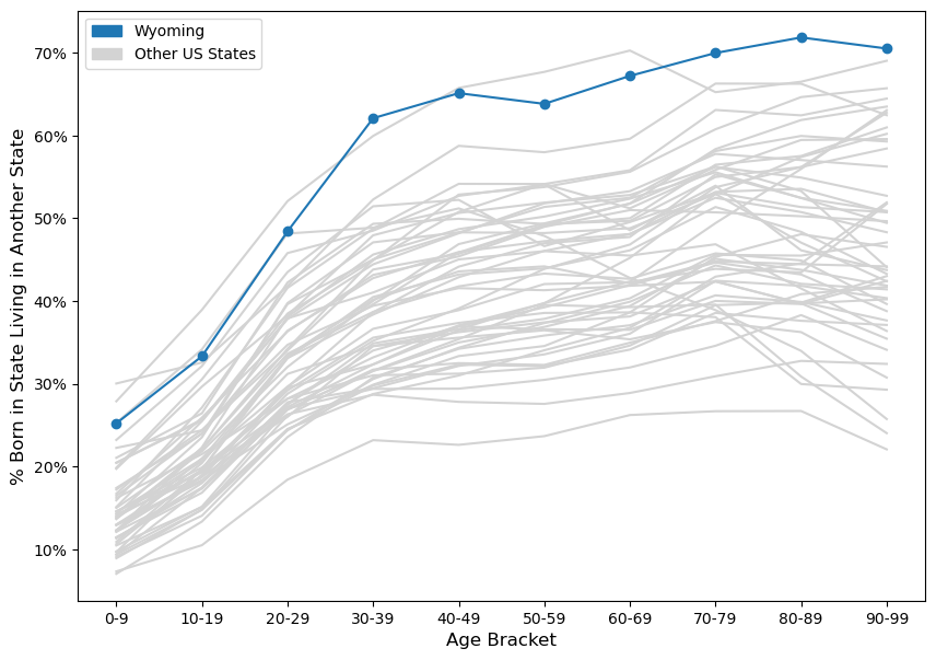

In reality, the Wyoming boomerang is a myth. Some individuals may move back to the state as they get older, but not in sufficient amounts to have a meaningful economic impact. Figure 1 shows the share of people born in each US state who are living in another state (as opposed to remaining in their home state) by age, with Wyoming highlighted in blue. If there was a strong boomerang effect, one would expect that the share of people living outside Wyoming would come down after a certain age. If anything, the opposite is true: older Wyoming-born people live outside the state at increasingly high rates.

Figure 1. Share Born in Each US State Living in Another US State by Age, 2022

Source: 2022 5-Year American Community Survey

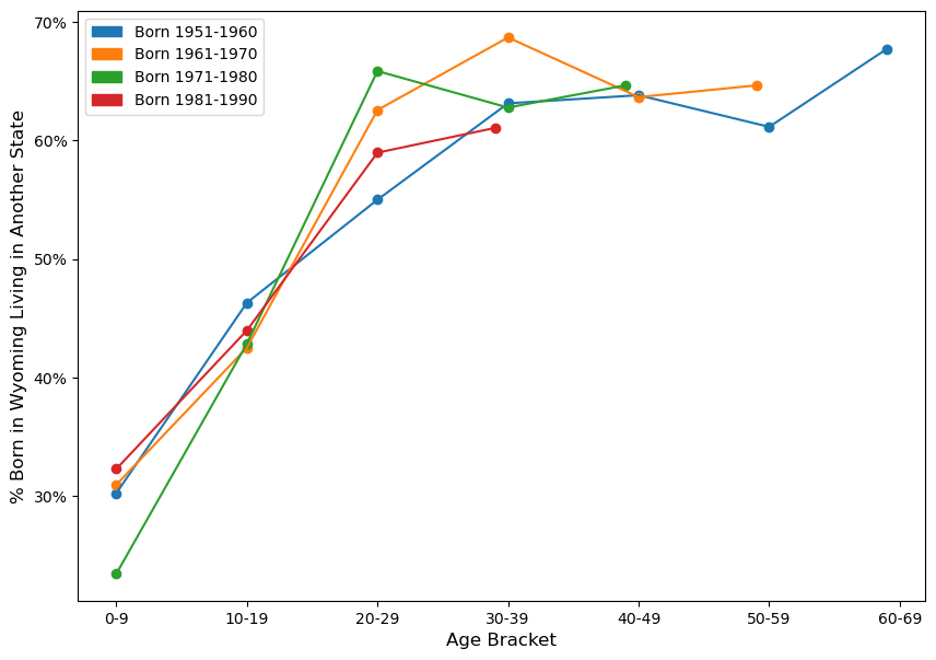

Another way of looking at the data is to follow different individual birth cohorts as they age, rather than a snapshot of all people in one year. Figure 2 follows people born in Wyoming in the 50s through 80s in the 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2019 US Censes as they age[1]. These birth cohorts are selected to ensure we observe people who have at least reached their 30s, so as to provide some meaningful time window for return migration in mature adulthood. Nevertheless, there is no significant boomerang effect in any of the four observed birth cohorts. All left at high rates in their youth, and did not return to Wyoming in substantial numbers thereafter.

Figure 2. Share Born in Wyoming Living in Another State by Birth Cohort over Time

Sources: US Censes and American Community Surveys, Years 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2019

On the whole, it is thus not accurate to say that there is any kind of substantial boomerang effect. People born in Wyoming instead leave the states at high rates into young adulthood, and on average do not return thereafter.

One consequence of Wyoming’s enormous exodus of young adults who do not return is that the majority of the state’s population was born elsewhere. Figure 3 shows a treemap of the birth locations of people living in Wyoming. Those born in Wyoming account for just 42.6% of the Wyoming population. The next two top contributors to Wyoming’s population are Colorado and California.

Figure 3. Treemap of Birth Locations of the Population of Wyoming

Source: 2022 5-Year American Community Survey

[1] We avoid the 2020 census because of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which could both induce irregular temporary migration patterns and statistical problems with the census sampling procedure itself. We instead use the 2019 census given that it is only one year beforehand.

Student Stories: Snowboarding and Labor Force Dynamics in the UAE

David Dam is a second-year MPP student at Harvard Kennedy School. He was accepted into the Growth Lab’s 2023 Summer Internship Program and contributed to the ongoing project with the United Arab Emirates – a multi-year initiative aimed at developing rigorous research to inform the UAE Ministry of Economy’s policies towards achieving sustained long-term economic growth and structural transformation.

Why did you apply to the Growth Lab Summer Internship?

The Growth Lab’s work aligned with many of my policy and research interests. I was especially excited about the UAE project given the country’s dramatic economic transformation over the past few decades. Additionally, I looked forward to collaborating closely with advisors within the UAE’s Ministry of Economy to gain exposure to another facet of policymaking where I could apply my existing skillset to an entirely different context. And of course, who could say no to spending an entire funded summer in Dubai?

What did you work on?

A focus of the Growth Lab UAE Project was on understanding productivity and labor force dynamics in the country. My main responsibilities over the summer included providing more insights to these workstreams. I worked on analyzing raw time series microdata of private sector firms and their employees using R and Python. This was such a fun collaboration navigating between the Growth Lab, Ministry of Economy, and Ministry of Human Resources and Emiratisation.

In what ways were you challenged?

I appreciated putting in the time prior to the actual summer internship to catch myself up on the ongoing project and familiarize myself with the economy of the UAE. Many of our policy research questions also required more creative thinking due to the lack of data granularity or reporting, in contrast to how I often took working with detailed U.S. economic data for granted. I enjoyed thinking about what traditional economic metrics tell us and what types of proxies we could use in place of them to yield additional insights and convey useful, actionable information.

What was your most exciting/surprising experience?

Besides learning how to ski and snowboard for the first time (you can truly find anything in the malls!) and witnessing the summer heat, I had the wonderful opportunity of briefing the Minister of Economy on the ongoing work and findings towards the end of my internship. I learned a lot from the preparation work, such as iterating on data visualizations and anticipating follow-up questions. I found myself putting many of the skills I learned from the first year of the MPP to good use!

What advice would you give to future interns?

Learn beyond the internship work! I took the time to explore Dubai and beyond over the ten weeks, and my conversations with both locals and expats gave me a much more informed view on the UAE’s labor market and high-growth industries. Time management and understanding what’s reasonable to accomplish within a 10-week period also helped me pace and organize my tasks, as well as balance work and fun!

What’s next for you?

I am finishing up my final year of the Master’s in Public Policy Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. I am incredibly thankful for my time at HKS, and I am really excited about all of the opportunities ahead!

Mixed Methods Valuable in Tackling Key Challenges in Wyoming

By Tim Freeman

Since August 2022, the Growth Lab has collaborated with the state of Wyoming to understand pathways to stronger economic growth across the state. The project, Pathways to Prosperity, has been conducted in close partnership with the Office of the Governor of Wyoming and the Wyoming Business Council in order to help state and local officials overcome key challenges. Together, we’ve examined Wyoming’s economic landscape, and further delved into problems within the state’s housing, grants, fiscal, workforce, and energy systems.

Wyoming’s wealth of reliable data has been instrumental to project work, allowing the team to extensively leverage quantitative analysis to explore barriers to economic growth across the state. However, we’ve found that quantitative methods have their limits, especially as one moves from studying the economy in aggregate to understanding issues and opportunities in smaller, local economies. This is especially relevant when digging into complex problems and change processes. Mixed methods—the pairing of qualitative and quantitative research—has been crucial to making real progress in Wyoming. This pairing has been a two-way street. At times, qualitative analysis has built upon quantitative findings, by providing an intuitive, real-world explanation for statistical outputs. Other times, qualitative research has guided our data analysis, with qualitative hypotheses tested against the data.

Leaning into mixed methods approaches has been particularly valuable in tackling two key challenges in Wyoming:

- Weak housing supply growth in the face of clear demand

- Severe difficulties that municipalities encounter in winning and implementing federal grants

The housing challenge in Wyoming is characterized by a shortfall of new residential construction. Demand for housing is rising across the state, but residential home builders face unique challenges and added costs in home construction. Identifying and now working to relieve those challenges to residential construction has relied on regression analysis and price elasticities to identify the most housing-constrained markets. The quantitative results worked in combination with iterative qualitative research between local housing stakeholders such as residential construction companies and city planners, with the goal of untangling the complex relations between housing policies, public goods provision, and private sector incentives.

The grants challenge centered on the underutilization of federal funds across the state, particularly in rural municipalities. Grants are one of the few lifelines for under-resourced municipalities to finance projects needed for community resilience and economic diversification, such as infrastructure, local capacity building, workforce training, and more. Our goal has been to identify and alleviate the hurdles Wyoming municipalities face in accessing the substantial federal grant funds available, including the challenges in crafting winning grant applications. Qualitative approaches became important very quickly in this work as quantitative analysis focused on the outcomes of grant applications, rather than the step-by-step process of winning and implementing grants.

Looking back at a year of work through the Pathways to Prosperity Project, a few lessons stand out regarding the mixed methods approaches key to our research:

History’s Staying Power

Policy is formulated to address current needs. However, policy designed to solve yesterday’s problems continue to be enforced today, even when said policy no longer matches present-day challenges. This policy holdover distorts the proper functioning of today’s markets and today’s public goods. Development researchers can use a historical lens to understand why certain policies are in effect today despite failing to address today’s needs. In the case of Wyoming’s grants system, the state’s institutional setup was designed to take advantage of federal funds as they were disbursed for the pre-2021 norm, primarily via state agencies. However, recent spending packages under President Biden asked communities to apply directly to federal agencies for access to the majority of funds, with Wyoming municipalities failing to adjust. This hypothesis was evidenced in part in official figures, showing that today just 20% of federal funds are disbursed via states, compared to 75% disbursement pre-2021. Understanding the historical origin of certain policies and how societal challenges have shifted allows researchers to gain an understanding on the mismatch between policy and today’s needs.

Positive Deviance

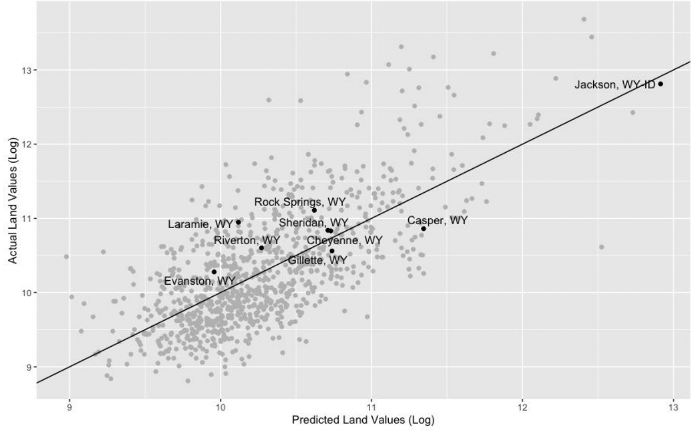

A surprising success story, such as the entrepreneur in a failing industry or the growing city in a struggling economy, offers insight into how other actors may overcome similar challenges. Positive deviance is the phenomenon of an individual agent overcoming a constraint holding back the broader group. Understanding the exact challenges surmounted and the mechanisms to success provide actionable insight into the fundamental nature of the development challenge, as well as a clue to what a feasible path forward may be. The housing workstream explored cases of positive deviance to understand why certain municipalities enjoyed cheaper residential land prices than the rest of the state. Although quantitative analysis allowed the team to identify the positive deviants (i.e. municipalities with cheaper residential land), deep dives into the positive deviants provided insight towards why certain land markets enjoyed cheaper prices than others. We found that positive deviant municipalities boasted robust arterial infrastructure, which allowed for a higher supply of land to be viable for residential construction, in turn lowering prices. In contrast, municipalities with high residential land prices struggled to expand their arterial infrastructure beyond city centers.

Gillette and Casper enjoy cheaper residential land than predicted. Both cities boast comparatively robust water and sewage systems. Source: Pathways to Prosperity Housing Note

Process Tracing

Quantitative analysis often overlooks dynamics within the change process, as numerical data tends to measure development outcomes rather than the process itself. Dissecting the underlying sequence of change with local actors elucidates when and where blockages impede the development process. Within our project work on housing, interviews with residential construction companies noted many issues that cropped up in the process of building a new subdivision. However, tracing the process of unsuccessful subdivisions identified two persistent blockages:

- When the developer was obligated to cover infrastructure costs that often are provided by the local government

- When the parcel was zoned to prohibit denser market-rate housing

Other difficult aspects within the construction process, such as finding a workforce, interest rate increases, or supply chain delays were problematic (and at times costly) but did not fully block construction. Conversely, we observed specific instances in which a parcel of land that was not hindered by these two blockages suddenly became available for sale. These cases enjoyed a comparatively smooth subdivision build-out.

Stakeholders as Analysts

Development researchers often do not belong to the society in which they are working. Although outside technical support is key for capacity-strapped governments, the loss of important local context should be minimized. The field can better leverage the contextual knowledge of local actors by incorporating a range of stakeholders into the research process itself. Local stakeholders add depth and uncover key insights often unseen by researchers arriving on assignment, such as providing intuitive explanations to data results. Better yet, any policy recommendation will be vetted for implementation feasibility and potential political support early in the research process. Our project work on grants grew out of biweekly task force meetings with grant applicants, grant funders, consulting firms, state government representatives, and local economic development officials. Joint research with the task force–including process tracing, discerning patterns in the evidence, trips to the field, and general brainstorming–ensured research findings leveraged the on-the-ground knowledge of stakeholders.

Concurrent and Existent Action Steps

When researchers take the time to explore what individuals and groups are already doing to try to overcome the problem, hard-won and innovative initiatives that could scale up or be stitched together often emerge. Similarly, piloting solutions oneself and iterating towards success identifies fundamental drivers of specific challenges and builds a targeted policy response. Problem-solving around the grants problem in Wyoming benefited from studying the different grant support programs already underway across the state, even though no existent initiative was intended to be a comprehensive solution. Key findings pointed to direct support as more useful than online webinars. Our team even worked through a live federal grant application with stakeholders to understand what type of support was most needed. Development research greatly benefits from studying action steps already taken to resolve the problem, as well as piloting initial solutions.

Growth Lab researchers visit the Wind River Indian Reservation in February 2023.

Targeted Surveys

The solution to a lack of targeted data can be to gather data, often quickly. Although a large-scale, fully representative survey is time-intensive and costly, surveys leveraging existing membership groups are straightforward and target a relevant group of respondents. Online tools such as Google Forms make the leg work minimal. Research on grants in Wyoming leveraged an existing state-wide conference on federal funding opportunities to run surveys with attendees, comprising grant writers and administrators from across the state. Although a state-wide representative survey would have been infeasible, our limited and targeted survey provided quick insights from relevant stakeholders with targeted research questions such as the number of staff dedicated towards grant writing, the grant sources they were most familiar with, and the prioritization of specific challenges in the process of winning a grant. The survey results were, in turn, analyzed with existing figures such as federal grant disbursement by municipality to give more complete and relevant quantitative analysis to pair with qualitative findings.

Targeted surveys allowed the team to gather pointed and unique data from key beneficiaries. Source: Pre-Summit Survey Results

Complex development challenges are only partially understood through data analysis. Mixed methods approaches have allowed the Wyoming team to explore constraints in the development process with added rigor and depth. Importantly, mixed methods not only allow for a more comprehensive analysis but facilitate policy action by building a sense of ownership among local actors. The relationships established during the research process develop the political capital and on-the-ground partnerships crucial for implementing proposed initiatives. Development researchers employing mixed methods approaches will dissect and address complex challenges with new clarity, ensuring their research leads to practical, impactful solutions.

Top photo: Growth Lab team members visit the Capitol Building in Cheyenne in September 2022.

Boosting future economic growth through diversification into more sophisticated industries: China, Viet Nam, Uganda, Indonesia and India leading the way

By: Timothy Cheston and Lorena Rivera León (World Intellectual Property Organization)

The journey towards economic development hinges upon the acquisition and utilization of productive knowledge, particularly in increasingly sophisticated – aka complex – industries and products. To chart a course toward robust economic growth, economies must effectively diversify into products that require rich and deep know-how which only a few other countries master, including innovation-intensive sectors such as information and communication technologies (ICTs), pharma, medical technologies, and different high-tech engineering products.

Embracing this premise, the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) of Harvard University, an indicator used in the Global Innovation Index (GII) 2023, evaluates economies’ competitive standing in terms of the advanced nature and diversification of their exports.

Based on this, Japan, Switzerland, Germany, the Republic of Korea, and Singapore top the rankings (see Figure 1). The Czech Republic, Austria, Sweden, Hungary and the UK (see Table 1) follow. The US ranks 12th.

Read the entire blog on Global Innovation Index Insights >>

Student Stories: Merging Data to Understand Emerging Global and Local Challenges

Rachel Chang is a second-year MPA/ID student at Harvard Kennedy School. She was accepted into the Growth Lab’s 2022 Fall and Winter RA Program where she helped construct visual stories that translate data and visualizations into timely insights for decision-makers.

Why did you apply for the Growth Lab RA position?

I applied to the Growth Lab RA position because I wanted to utilize the findings from the Atlas of Economic Complexity and Metroverse to create compelling data-driven visual stories. The Growth Lab RA position was a great way for me to contribute my product management experience, along with the analytical frameworks and economic rigor from the MPA/ID curriculum.

What did you work on?

I generated three distinct story concepts and eventually focused on Taiwan’s need for diversification beyond chips and semiconductors. This involved conducting outside research, using the Atlas of Economic Complexity and Metroverse, and working closely with the Growth Lab team.

In what ways were you challenged?

I was challenged because I wanted to connect country-level data from the Atlas and city-level data from the Metroverse to create a cohesive narrative for Taiwan. This was challenging because there wasn’t a clear connection between the data.

What was your most exciting/surprising experience?

The most exciting part was finding a way to bring the Atlas and Metroverse data together in a seamless manner. I was thrilled to see this piece come together using analytical economic methods and crafting a narrative.

What advice would you give future Growth Lab interns/RAs?

I would advise future Growth Lab RAs to supplement their RA-ship with courses, such as API313M: The Tools and Methods of Economic Complexity Analysis and DEV 309: Development Policy Strategy. The Op-Ed writing class at HKS was also especially helpful in providing best practices for writing compelling pieces (for those interested in writing short stories for the Growth Lab). The technicalities learned from these classes were directly relevant to my project analysis!

What’s next for you?

I’m further inspired to utilize data as a means to explore international economic growth opportunities and to bridge both the micro and macro aspects of economic advancement. I hope to continue working on these topics after graduating from the MPA/ID program.

Setting the Grounds to Measure Smallholder Farmers’ Complexity

By Laura Romero

The Growth Lab has estimated economic complexity, a measure of knowhow agglomeration, for several countries worldwide. However, measuring complexity in the agricultural sector poses a significant challenge. What is more, measuring it for smallholder farmers around the world is even more complex. Through our work, we have laid the groundwork for future measures of complexity for this population.

I joined the Growth Lab Agriculture Initiative last October, aware of how challenging it would be to answer this question. We started with the basics: Who are the small farmers? If you ask someone in India and someone in Albania, I assure you that the answers will diverge. In fact, the literature recognizes that smallholder farmers are a heterogeneous group (Ethical Trading Initiative, 2005; FAO, 2012). Some of the variables in which they differ include the following:

Typically, smallholder farmers produce relatively modest volumes of goods on small plots of land. They are generally less well-resourced, vulnerable in supply chains, and have limited access to markets and services. The most common criteria used to define smallholder farmers globally is land size, with a consensus that they work on land plots smaller than 2 hectares (Committee on World Food Security, 2016; FAO, 2012).

With this in mind, we explored worldwide data on these population. The most comprehensive datasets are published on the FAOSTAT statistics website, which contains information for over 145 countries. Relevant databases include Structural Data From Agricultural Census and Production Crops and Livestock Products (FAO, n.d.). By calculating comparative advantage indicators to get information on the productive capabilities, we determined that some countries have comparatively more smallholder farmers than others. These countries include Guatemala, Albania, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, Namibia, and India, among others.

Furthermore, using a programming function, we were able to determine the revealed comparative advantage (RCA) by crop and country for three time periods: 1990, 2000, and 2010. We also estimated which crops were the top five produced by each country and analyze whether these had comparative advantages with respect to the region.

Since worldwide information about country and hectares harvested for each crop is not available by land size, the next step was to compare the top five most produced crops by country and its RCAs with national information. For a subset of six countries, we analyzed which crops were most commonly harvested by smallholder farmers, using Agricultural Censuses of National Surveys. The countries are Guatemala, Colombia, Albania, Ethiopia, Namibia, and South Africa.

Guatemala and Albania stand out as countries with relatively more smallholder farmers’ land with respect to their respective regions, as well as to the set of developing countries in the world. In the case of Guatemala, coffee, sugar crops and maize are three out of the five most produced to display a comparative advantage with respect to Latin America. According to the country’s national survey, coffee and maize are among the most harvested crops by smallholder farmers (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica [INE], 2013). In the case of Albania, there are comparative advantages for cereals, pulses, and wheat, all produced by smallholder farmers (Institute of Statistics [INSTAT], 1998).

Colombia also has relatively more smallholder farmers’ lands compared to the other countries in the continent. Coffee, fruit, and rice are some of the most harvested crops in the country, with comparative advantages over other crops. From these, coffee, banana, and plantain are the most frequently harvested crops by small farmers (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadistica [DANE], 2014).

Top 5 crops produced by country: Share and RCA – 2000

In Africa, Ethiopia and Namibia are highlighted as countries that have relatively more smallholder farmers’ land concerning their respective regions, as well as the set of developing countries in the world. In Ethiopia, cereal crops and wheat are two of the most produced to show a comparative advantage. According to the country’s Agricultural Census, cereals like teff, sorghum, barley, and wheat are among the most harvested crops by smallholder farmers (Central Statistical Agency [CSA], 2012). In the case of Namibia, there are comparative advantages for edible roots, cereals, and specifically millet. Indeed, millet is one of the most commonly harvested crops by smallholder farmers, along with sorghum (Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Rural Development [MAWRD], 1995).

Finally, South Africa stands out from other African and developing countries due to its relative lack of smallholder farmers’ lands. The countries’ top five harvested crops have a comparative advantage compared to the region. There are sunflower seeds, wheat, sugar cane, cereals, and maize. From these, smallholder farmers produce maize and sugar cane (Statistics South Africa, 1997).

Top 5 crops produced by country: Share and RCA – 2000

There have already been initiatives aimed at prioritizing specific products for smallholder farmers to integrate into local and global markets. One example is Japan’s One Village, One Product program, which was developed in 1979 to increase the value of locally produced goods and boost household and national income. The program targeted farmer groups and cooperatives, with one village sometimes prioritized. This public policy has been replicated in several countries (FAO, 2013).

More recently, the FAO launched the One Country Priority Product (OCOP) initiative to promote special agricultural products with unique qualities and characteristics. This project places smallholders and family farming at the center of interventions to improve access to stable markets and serve as a key entry point for achieving their defined priorities (FAO, 2022). Numerous countries have already defined which products to prioritize, taking comparative advantages into consideration. From the countries we analyzed, Guatemala prioritized coffee and Ethiopia prioritized teff.

Overall, we have laid the groundwork for future measures of complexity for smallholder farmers around the world. We have developed a methodology that uses comparative advantages to identify existing capabilities in different economies. We identified who the smallholder farmers are, where their lands are predominantly located, which crops are most harvested, and whether they display comparative advantages. Additionally, we have presented some initiatives that propose the prioritization of certain products to integrate smallholder farmers into local and global markets. Mapping the existing capabilities of different types of farmers and crops that diverge in productivity is a crucial first step in discussing economic complexity in smallholder farmers.

References

Central Statistical Agency. (2012). Statistical report on the 2010-2011 agricultural sample survey. Volume I: Statistical report on crops (private peasant holdings). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Retrieved from https://catalog.ihsn.org/catalog/1389/related-materials

Committee on World Food Security. (2016). Connecting smallholders to markets. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/3/bq853e/bq853e.pdf

Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. (2014). Censo Nacional Agropecuario 2014: Resultados nacionales. Retrieved from https://www.dane.gov.co/files/images/foros/foro-de-entrega-de-resultados-y-cierre-3-censo-nacional-agropecuario/CNATomo2-Resultados.pdf

Ethical Trading Initiative. (2005). Recommendations for Working with Smallholders. Retrieved from https://www.ethicaltrade.org/sites/default/files/shared_resources/eti_smallholder_guidelines_english.pdf

FAO. (2012). Coping with the food and agriculture challenge: smallholders’ agenda. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/nr/sustainability_pathways/docs/Coping_with_food_and_agriculture_challenge__Smallholder_s_agenda_Final.pdf

FAO. (2013). Global application of the One Village One Product Movement concept: Lessons from the experiences of the Japan International Cooperation Agency. Rome, Italy: FAO. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3251e.pdf

FAO. (2022). The Global Action on Green Development of Special Agricultural Products: One Country One Priority Product Action Plan 2021-2025. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/cb5506en/cb5506en.pdf

FAO. (n.d.). FAOSTAT. Retrieved March 23, 2023, from https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data

Institute of Statistics. (1998). Albania – Agricultural Census 1998 – Main Results. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ess/documents/world_census_of_agriculture/main_results_by_country/albania_2000.pdf

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (2013). Guatemala – Encuesta Nacional Agropecuaria 2013. https://www.ine.gob.gt/encuesta-nacional-agropecuaria/

Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Rural Development. (1995). Namibia Agricultural Census 1995 – Main Results. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/publications/card/es/c/8dc4e39c-6b78-4ddf-889c-180389c24900/

Statistics South Africa. (1997). South Africa Rural Survey 1997. Retrieved from https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/1602