The Growth Lab is Seeking Applicants for Fall Semester Research Assistants

The Growth Lab is growing! As the fall semester begins at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), the program is launching and expanding several efforts across its applied research project portfolio, academic research focus areas, and development and application of its digital tools. The program is looking for current students from across Harvard to join through a new part-time research assistant program. Effort is expected to be 5-10 hours a week, depending on the opportunity and individual circumstances. Many of these RA roles may continue beyond the fall semester through January and spring semester 2023. These roles span across a variety of topic areas, types of work, and required qualifications. What they have in common is that each is a new frontier of Growth Lab work in the world, and each offers an opportunity for outsides-the-class learning.

We encourage any students who are interested in applying what they are learning in class to pressing growth and development challenges to review this listing of fall semester RA opportunities and consider applying. The deadline for applications is Friday, September 30th.

Here is an overview of the opportunities. Please see the call for applications for more detail on each and instructions for how to apply.

Data-Driven Visual Stories: Growth Lab interactive data tools provide a wealth of information to understand emerging global and local economic challenges. We are looking for several students to help teams of researchers and digital developers to construct data-driven stories (see example) that translate data and visualizations into timely insights for decision-makers. Students will likely focus on the Growth Lab’s new Metroverse as well as its more widely known Atlas of Economic Complexity.

Green Growth: As the world decarbonizes, new technologies will create profound economic opportunities for many economies, including those of developing countries. Actions now and in the coming years by policymakers and the private sector will go a long way to determining to what extent their societies benefit from decarbonization-induced economic transformation. We are seeking candidates to help us create a knowledge graph that bridges scattered knowledge of low-carbon green transitions and enable a holistic view of opportunities and risks for green growth via the integration with economic complexity methods and tools. We also welcome broader expressions of interest in line with green growth (see background here and here.

Growth Miracles: Long-term economic growth that allows previously low-income economies to enjoy greater and greater levels of economic opportunity is the hope for all poor economies today. Economic growth miracles are rare, but they do happen. We are looking for RA support to help us better understand the relationship between economic complexity and growth miracles around the world.

“Genotypic Approach” to the Product Space: The Product Space is a mapping of the relatedness of products by the underlying capabilities required to produce them competitively. Because of the nature of global data, the Growth Lab has been limited to understanding these capabilities through a “phenotypic approach” where we can observe what all economies produce but not capabilities themselves. A “genotypic approach” on the other hand starts from data on input requirements by industries and uses this data to analyze industry-similarities and patterns of entry into new industries by countries, among others. We are looking for RA support for our academic team in compiling and analyzing data that is informative for the genotypic approach.

Book on Economic Complexity: Professor Ricardo Hausmann has been recording his thoughts on complexity on Zoom sessions around a book outline related to economic complexity. We are seeking an RA literate on economic complexity thinking to transcribe and create a first draft of the chapters. This is a unique opportunity to contribute to the codification of years of academic and applied learning in an exciting new field.

>Smallholder and Collective Land Agriculture: While climate change and other new stresses put increasing pressure on smallholder agriculture, experiences from across several Growth Lab projects have underscored the power of organizational models that bring knowhow and inputs together in ways that allow smallholder farmers to participate in competitive value chains — allowing them to reach new markets, increase incomes and gain resilience. Organizational challenges to these models emerge in situations of collective land ownership, but many forms of partnerships have overcome these models, including in South Africa. We are seeking a team of students to help us develop tools for understanding and developing more of these opportunities.

The Role of Remoteness: The Growth Lab is developing a flagship report on the development effects of — and policy responses to — remoteness. We are hoping to incorporate students to help us develop a comprehensive review on the broad academic and policy literature on the matter at the national, regional, and urban levels. We also want to incorporate students to help us with complementary data analyses regarding our work on trade and telework. Students may focus on literature review or data analysis, or both depending on experience and interest.

Building Globally Comparable, Locally Precise Data: The Growth Lab is developing a set of “glocal” datasets (globally comparable, locally precise) on a number of economic, ecological, demographic, and political markers. We are looking for students to help us incorporate different sources to create additional variables to add to the final dataset. Also, we want to incorporate students to help us scrape data from online sources and process them to generate additional “glocal” fields to add to the final dataset.

Crime Data Visualization: Researchers in the Growth Lab are currently engaged in research regarding the economic and enforcement determinants of violence. To better enable the assessment of a set of unique datasets on the matter, we want to incorporate students to help us develop a data visualization dashboard of specific characteristics, under the supervision of both our research and our visualization teams.

Venezuelan Refugee Crisis: The Venezuelan refugee crisis is of a similar magnitude to the Syrian and Ukrainian crises. To better assess its economic and political effects on host communities, we want to measure and predict migration patterns during the Venezuelan Refugee Crisis. Importantly, we want to assess whether patterns of ecological similarity between home and host communities help predict bilateral moves.

Political Favoritism: In studying how autocrats distribute rents in pursuit of regime stability, we want to gather, develop, and analyze a diverse number of datasets with the help of our students. These involve, but are not limited to, the distribution of power generation equipment, national budget transfers and government appointments during the Venezuelan economic crisis of 2014-2019. The work also implies supporting the writing and literature reviews for several research projects in the same setting.

A Hamiltonian moment for Europe? Demystifying Next Generation EU and the EU’s recovery funds

The Next Generation EU (NGEU) programme represents a milestone towards fiscal mutuality against common shocks in the EU, changing the way the Union finances itself. This is why the LSE European Institute hosted a panel event aimed at bringing together experts from a wide array of experiences to explore the design and implementation of the NGEU, weighing the positives against the negatives.

In this blog, Renato Giacon and Corrado Macchiarelli give an account of the discussion that took place on March 9, 2022, at LSE.

The Next Generation EU programme is changing the way the EU finances itself as never had the European Commission borrowed at such large scale and long maturities on financial markets. Meanwhile, six EU Member States (Italy, Greece, Romania, Portugal, Slovenia and Cyprus) have decided to make the leap of faith and have included a formal request for concessional loans in their adopted Recovery and Resilience Plans, counting to overcome their large funding needs post Covid-19 but also a decade of low investment expenditure.

The LSE European Institute organised a panel discussion, focussing on how NGEU and the EU Recovery Fund (EU-RRF) should be designed and implemented to (i) better focus on effective, efficient, equitable and sustainable ways of spending EU and national money for bankable projects; (ii) successfully mobilise private sector funding from institutional investors, International Financial Institutions (IFIs) and commercial banks; and (iii) deliver the promised medium to long-term benefits in terms of economic convergence, complexity and higher growth patterns that EU countries can derive from it.

The national Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRPs) – that each EU Member State (MS) is asked to compile and stick to – are embedded in the European Semester, the EU’s framework for economic policy coordination, with grants and loans’ payments to EU MSs released only upon the successful implementation of performance-based milestones. These are defined both in terms of investments and reforms, with the additional request to achieve ambitious green and digital targets. Such an enhanced policy steering at the EU level must balance different national agendas driven by often competing political economy needs. The mechanism represents a strong external market discipline both in the funding and the investment framework, which finds a precedent only in the experience of some EU countries such as Greece under the Enhanced Surveillance Framework post-2010.

The discussion opened with the remarks of Ines Rocha (EBRD) who built her intervention on the operational insights provided by the active role of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in the implementation of the NGEU programme and the deployment of the Recovery Funds. She made the point that large RRF grant-funded projects are usually included ex-ante in countries’ RR Plans, while smaller projects that are part of broader investment programmes might be selected through public tenders or similar procedures. Private sector projects to be financed via RRF loans mainly depend on the IFIs, national promotional banks and commercial banks’ pipelines, creating an important private sector-led investment stream in the implementation of the programme.

Furthermore, EU countries – which have requested EBRD engagement in the delivery of their RRPs – have recognised that EBRD is strategically aligned in its own priorities and country strategies with the national Recovery Plans. The EBRD can assist the countries in delivering policy objectives and leverage the EU recovery grants and loans by attracting other private co-financiers to facilitate successful programme delivery.

The most typical sectors of EBRD intervention include the areas of:

- Green growth (such as financing renewable energy, electricity storage projects, hydrogen production, green cities, clean mobility and energy-efficient buildings’ renovation)

- Accelerating the digital transformation (5G, gigabit networks and fibre optic networks, broadband projects, digital upskilling and reskilling programmes, support for the digitalisation of businesses with a particular focus on SMEs, start-ups & greater cloud usage)

- Financing R&D and innovation projects outside the digital sector such as in the field of climate innovation (i.e. fertilisers, cement sectors).

She ended her intervention by pointing out that the most concrete EBRD engagement under the Recovery Funds so far has been in Greece through the Corporate Loan Facility. The programme will combine up to €500 million of RRF concessional loans managed by the EBRD, up to €500 million of EBRD commercial own-resources financing and financing from private investors and commercial banks. The EBRD signed an Operational Agreement with the Greek Ministry of Finance in November 2021. From the point of view of project structuring, the Greek RRF Facility is unique insofar promotes financial discipline by private sector final beneficiaries which have to pay back the loans, encourages proper risk assessment by market players in the absence of Greek state guarantees and leverages RRF funds through co-financing with private sector funding sources.

Some of these points were picked up by Professor Anthony Bartzokas (LSE Hellenic Observatory and the University of Athens), who singled out the NGEU as a new important tool to support investment recovery in the EU, funded through the Commission’s borrowing on the capital markets. Furthermore, he emphasized the early positive signals from markets with NGEU-related announcements already demonstrating a significant spread-compressing effect on euro area sovereign borrowing costs. In addition, Bartzokas recognised in his intervention that the investment stimulus provided by the EU recovery funds includes fine-tuning opportunities in response to concerns about European resilience, especially at a time of elevated geopolitical risk and green transition uncertainties such as the current one.

He continued by identifying a few possible implementation gaps in the EU Recovery Funds linked to the focus on thematic clusters with limited microeconomics considerations, the need for detailed cost justifications during project cycles, and overlaps vs. complementarities with the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIFs) and EU cohesion policy. Particularly, he highlighted how the experience of ESIFs and other existing EU funding programmes has already driven the evolution of investment decisions of different policy institutions at different governance levels (i.e., European Commission, the EU member states, IFIs and private sector’s financiers) and advocated a similar learning process in the governance processes of the EU-RRF. Finally, he underlined some legacy issues identified from the EU Cohesion Policy experience in the academic literature, including the lack of timely implementation, limited project upstreaming capacity and a funding substitution effect for the national budgetary component, as important priority areas for the monitoring function of the EU-RRF in the implementation phase.

Vedrana Jelusic Kasic (Privredna banka Zagreb) brought a private sector experience to the panel, both in her role in the Management Board of Croatia’s second-largest commercial bank and former regional Director at EBRD with the lead on projects in Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary and Slovakia. She shared her direct experience co-financing with the ESIFs and provided insights on how the new EU-RRF will be different in terms of effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability.

She highlighted how the past experiences with EU funds had not always delivered to the initial expectations due to a combination of various reasons, such as:

- Cumbersome reporting requirements

- Lack of coordination between EU co-funded programmes and the national programmes

- A lack of bankable projects which would have required a need of technical assistance funding for project preparation and implementation support

- A legacy of poor absorption capacity from Managing Authorities which would have required improvements in the quality of government and the enhancement of administrative capacity

- A realisation that the type of expenditures under European Funds had often given priority to basic infrastructure projects, instead of also trying to prioritize the advancement and reconstruction of the productive environment and the support of investments.

However, she also offered a positive way forward in pointing out that the experience with EU funds in the previous EU budget has served as a lesson in the design of the new EU-RRF which have a few in-built advantages that need to be translated from design to implementation. The release of funds is performance-based with a clear set of reforms and investments’ milestones which create clear incentives for EU MSs to deliver on their EU-RRF commitments. Secondly, the funds focus on two clear strategic priorities, the green and digital agenda, which are aligned with the key implementing partners’ agendas and should avoid “spreading the funds too thin” on the ground. Finally, EU-RRF leaves autonomy to the EU MSs to set their own country-specific reform and investment priorities, while letting implementing partners set up their financial structures at the operational and implementation level.

Finally, Dr Frank Neffke (Complexity Science Hub Vienna, Growth Lab Associate) focused on economic complexity and the lessons of economic geography as a cornerstone of economic recovery and growth in the post-Covid-19 EU. He made the point that geography still matters, especially for trade and FDIs flows. He highlighted how “path-breaking growth” would often require the ability of attracting high-skill workers, as well as the ability to generate return migration: low skill workers that move from advanced to less advanced economies (e.g., Albanian return migrants from Greece; Yugoslavian returnees from Germany, etc.). FDIs could help the required investment in skills where foreign firms could help kickstart new tech hubs. In that sense, the mix of policy reforms and higher investment volumes through EU-RRF should be able to increase economic complexity.

He finally pointed out that lessons a sustained and sustainable economic recovery should include priorities such as:

- A transition to a green economy that leverages the capabilities that currently exist and are used already in their economies

- Investments in skills and skill ecosystems

- An exploration of local economies’ “adjacent possibles”

- Aiming for higher complexity

- Focus on connectivity & digitization, return migration and smart inward FDIs

To conclude, there are a number of points worth emphasising about the status and design of Next Generation EU and the EU’s recovery funds. First, this new EU initiative brings together three relevant and interrelated dimensions of consensus-building (fiscal, rule of law, and policy priorities around green and digital). Second, it is innovative insofar as it is strictly tied to an ongoing monitoring and conditionality mechanism of tranches of EU funds being disbursed upon the achievement of clear milestones.

Third, it is timely as it opens the way to other future large scale European Commission borrowing plans, including as part of a response to current EU energy and defence investment needs following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Fourth, it highlights the agency and ownership of national authorities in the design and implementation of their national plans but also their reliance on international financial institutions such as the EBRD for co-financing with their own balance sheet, mobilising private financing, managing technical assistance and helping with unlocking policy reforms.

Fifth, it will help EU member states (like Greece) to achieve higher economic complexity, facilitate further integration in European supply chains, invest in skills and ecosystems, and to explore the appropriate green capabilities and attract foreign direct investment.

Sixth, it shows how policymakers in Southern European countries such as Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal have reflected on lessons learned from the previous euro area sovereign debt crisis, taking reforms and investment milestones seriously and moving ahead of the EU pack in the implementation of their Recovery and Resilience Plans and further disbursements of Recovery and Resilience Facility tranches.

These countries have been the first cohort of EU member states whose plans have been approved by the EU Council. Spain, France, Italy and Greece have all also received the European Commission’s positive preliminary assessments of their second payment requests based on the achievement of several milestones which cover reforms and investments in various areas (energy efficiency, electric mobility, waste management, labour market, taxation, business environment, pensions, healthcare, public transport, and many others).

Finally, and as a counterpoint, special attention ought to be paid to some Central and Eastern European countries where investment needs are high but there are still some delays in the implementation of the plans and the flow of new funds into their economies. Given past problems of scarce absorption capacity and bankable projects, the role of international financial institutions such as the EBRD as well as the European Investment Bank and national promotional banks has become increasingly linked to the success of this new pan-European funding and policy initiative, at a scale unheard of in the history of the EU.

This blog was originally published on LSE EUROPP.

15 Visual Insights from the Growth Lab in 2020

The Growth Lab has over 50 faculty, fellows, research assistants, and staff working on development challenges in more than a dozen countries worldwide. Our research in 2020 included modeling pandemic-related tradeoffs, mapping the network of global business travel, identifying foreign exchange constraints in Ethiopia, tracking the migration of the Albanian diaspora, and uncovering environmentally friendly diversification opportunities in Peru. Every project, paper, and presentation brought hundreds of charts, graphics, dashboards, and prototypes. We thought it would be worthwhile to share some of our more notable visual insights from this year.

Learning Policy in Practice: Insights from the Growth Lab Summer Interns in Albania

PDIA in Sri Lanka: Evaluating Potential Sites for New Industrial Zones

Originally published by the Building State Capability blog – Priyanka Samaweera

Through the comprehensive analysis conducted, the Targeting Team was capable of identifying priority sectors for attracting investment and enhancing the exports of Sri Lanka. The next task was to identify suitable lands for establishing factories in these sectors, especially given that over 89% of the Export Processing Zones (EPZs) of the BOI are already filled. Since limited access to productive land for the potential Investors can be considered as one of the most important limiting factors to attract investments, due consideration should be given to resolving land issues prior to marketing priority sectors to the investor.

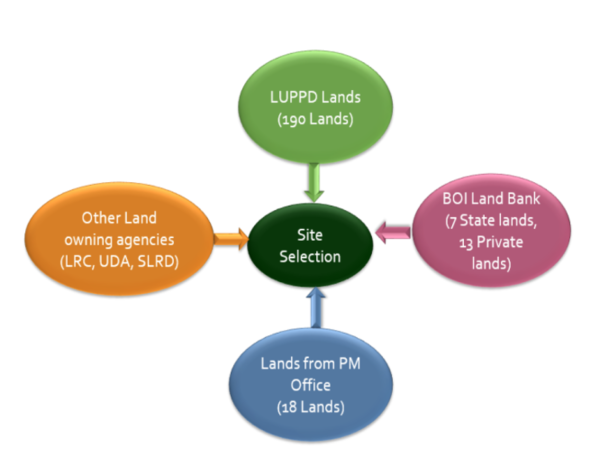

Having identified the problem, the Land Team began gathering information on available lands for investment projects. It was noted that the state owns over 80% of land in Sri Lanka, though this ownership is spread over at least ten different Ministries and Departments. The team met with many of these bodies, ultimately creating a database of over 600 available lands (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Lands from multiple GoSL bodies considered

The list of over 600 sites was then restricted to those with more than 50 hectares in extent (with later work focusing on the smaller sites). Next, an assessment based on satellite imagery (Google Maps) was conducted to determine each land’s suitability for further investigations. Based on this assessment, over 70 field visits were conducted to gather field data for final assessment. This field data, as well as sector expertise, formed the inputs for the analysis of land suitability for target sectors, conducted according to a sector-location methodology developed by the Team (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Stages of the site evaluation and selection process

Assessing the Sector Requirements: A Sector-Location Methodology was developed to assess the suitability of the lands for an investment in a priority sector. First, the hard and soft asset requirements for each priority sector were obtained from the Targeting Team asset competitiveness analysis, in which sectors with a higher requirement for a land characteristic received a higher weightage. However, the Team also added new land characteristics that were required equally by all sectors, such as topography and development cost.1 Accordingly, an overall weightage was given to each land characteristic; these fell into four categories: hard asset availability (45% of total weightage), soft asset availability (18%), general conditions (14%), and accessibility (13%).

Assessing the Land Characteristics: Next, a set of scoring criteria was developed for each land characteristic, seen in Table 6. Each site was assigned a score between 1 to 5, considering field-level observations, available district-level data (for labour characteristics), and expertise of the Team members. For example, if a particular land is more than 400 acres in extent, then a score of 5 was assigned, whereas a land with 75 acres or less was given a score of 1. This matrix was filled for each land identified for the assessment, which included existing BOI Zones as well.

Then the two matrices – land characteristics and sector requirement – were multiplied to generate a final scoring for each land for each sector. The scoring was between 1 and 5: a score of 5 signals that the land is a perfect match for the sector in terms of the land characteristics the sector requires; scores under 3 were taken to mean that the land is not suitable for the sector. The average score of each land for the T Team’s top 12 full sectors were calculated. Based on this analysis, 29 sites with an average scoring value above 3 were identified and were prioritized.

The Outcome: Out of the prioritized lands, the top-ranking locations were recommended for development into EPZs (Figure 3). A separate detailed report (focusing on the list of lands given by the Prime Minister’s Office) was also submitted, prioritizing the suitability of those lands for investment projects. Ultimately, the 2018 Budget allocated funding for zones, and development is underway in four identified sites so far (including one as a PPP).

Figure 3: Locations of lands in development (green) and other top-ranked lands (black)

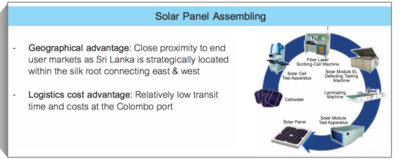

PDIA in Sri Lanka: Attracting Anchor Investors in Solar Panel Manufacturing

What It’s Like Working as a Research Fellow at the Growth Lab

CID’s Growth Lab is a dynamic program driven by faculty, fellows, and research assistants who are seeking to understand the facets of economic development and to uncover how countries, regions, and cities can move into more productive activities. Our Research Fellows are integral to the success of the Growth Lab: the role’s responsibilities range from research in Cambridge to field work across the globe, and interactions with government officials.

Led by Ricardo Hausmann and a diverse, interdisciplinary team of research fellows, our work takes us around the world. Current projects include Albania, Ethiopia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela.

Tim Cheston, Semiray Kasoolu, Shreyas Matha, Ljubica Nedelkoska, Miguel Santos, and Nikita Taniparti share their perspectives on the role of a Research Fellow.

What led you to CID’s Growth Lab? Why did you want to work here?

Shreyas Matha: After graduating with my masters, I was looking to work at a place that addresses public policy questions but did not restrict itself solely to techniques in traditional economics. What appealed to me most about working at the Growth Lab was that the place is open to embracing experiments in newer techniques such as natural language processing and machine learning.

Semiray Kasoolu: The Growth Lab is a place of independent thinkers who are not afraid to use a holistic methodology to diagnose different development problems. And to me that freedom of research meant a lot. Another thing that really impressed me was the efficiency of deployment of those research findings to developing countries and to the counterparts in those countries. And that also really impressed me because that is very different from what I know about other development institutions.

What stands out about the Fellows role at the Growth Lab? What is your level of engagement with policymakers?

Tim Cheston: The fellows really are the front line of applying these ideas in the field, and they have a range of expertise and specialties and analyzing different data sets and applying them to different policy purposes. Traveling to Colombia, Mexico, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia, and working hand in hand with ministers and technical staff across all of those countries has been a real privilege, to see both the larger struggles that unite all of those countries but also the unique features of each one of those places.

SK: The role of a fellow at the Growth Lab is unique in that it combines three things. One is using quantitative methods to discover and probe for development problems. The second one is to validate those with field work and field trips. And the third one is to use those the first two to come up with policy implications and inform of policy work.

Ljubica Nedeloska: I had the opportunity to engage with policymakers on both the technical level and the policymaking level and also on a variety of issues such as employment strategy, disapora relations, fiscal projections, employment projections, fiscal policy among other things. This experience gave me a very interesting chance to see inside how governments work. And I think this is very unique to the GL and I don’t think it would have been possible to learn if I would have stayed in solely academia.

Nikita Taniparti: You’re doing research–you’re reframing the way that governments and policy makers ask questions… You get to interact with the minister or the government, and you hear why they can’t just do the easiest policy option that you might think they should be doing.

What is your favorite part about working at the Growth Lab?

LN: What I like most about working at the Growth Lab is the interdisciplinary teams of highly motivated and highly talented fellows. I also enjoy working with some of the most brilliant minds in the field of economic development. This place has high energy and also high optimism which I enjoyed very much. And last but very important, I recently became a mom and the Growth Lab specifically offered very reasonable conditions for work/life balance.

SM: I’d say my favorite part about working at the Growth Lab is that I get to work with a floor full of postdocs and Ph.D. students who are all interested in working on questions in public policy but also coming at them from new and interesting perspectives.

NT: The Growth Lab is where you get this chance to use your intellectual curiosity to ask the questions that really matter. You’re not just working on a really small part of something where you don’t know the outcome. Our research questions that can be very theoretical are all driven by something that’s happening in the world. We know exactly who we’re working for, whether it’s farmers on the ground or foreign workers in a different country. You know why you’re asking the question and why you’re asking it the way you do.

Miguel Santos: I like arriving in a location you know very little about, with a team of highly qualified people that challenge you constantly, and gradually learning about that place. This process of learning the nuances of a country and translating that into policy, and having the capacity to surprise people who have been there a long time, that’s my favorite part of the job.

This Q&A was edited for clarity and brevity.

What It’s Like Working as a Research Assistant at the Growth Lab

Harvard’s Growth Lab is a bustling hub of faculty, fellows and staff working to understand the dynamics of economic growth and uncover how countries, regions, and cities can move into more productive activities.

Led by Ricardo Hausmann and a diverse, interdisciplinary team of research fellows, our work takes us around the world. Current projects include Albania, Ethiopia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, and Venezuela.

Research Assistants also play a fundamental role on our team. Not only do they provide research support by analyzing and managing datasets, they also collaborate with our high-level counterparts, offering comparative analysis of policies.

Three current RAs Sehar Noor, Bruno Zuccolo, and Ana Grisanti share their perspectives on what makes the position unique.

What led you to CID’s Growth Lab? Why did you want to work here?

Sehar Noor: CID is really at the frontier of a lot of the topics that I was interested in as an Economics major in undergrad. Everything from growth diagnostics to complexity work, it’s looking at diversification from a unique perspective, and I was drawn to both the faculty and the research that is produced by the fellows here.

Bruno Zuccolo: What I really liked about the Growth Lab was the intersection of researchers working on the very academic side of learning about growth, but also a very dedicated team of fellows and research assistants applying that research in country projects. The country projects are varied and work through very different economies; when I first joined I was working on projects in Albania and Argentina, and I was working on issues of growth in all those countries. I think this was a fantastic opportunity to learn about countries that I didn’t know that much about and to be able to apply rigorous methodology and statistical analysis.

What stands out about the Research Assistant role at the Growth Lab?

Ana Grisanti: I have many responsibilities, ranging from data cleaning and the visualization of the data, to finding out who we want to interview in the field and going into the field and engaging in interviews with counterparts. One of the states within Mexico that we were working on was Baja, California, and we were doing a growth diagnostics and complexity analysis in the state. The second time I traveled to Baja, I had the opportunity to present our findings to our counterparts, which was a thrilling experience for me. I think that’s unique for the RA position at CID and one I would not have at any other center.

BZ: What I like about being an RA at CID’s Growth Lab is that you’re working on multiple projects at once, and that means you get to explore a lot of issues specific to each country. So in Albania, where I’ve worked for the past year, we work on issues of agriculture, macro growth, trade, and tourism, and as an RA you don’t always get the opportunity to delve into as many issues as this. The other thing about being an RA that’s fantastic is going to the field. At CID, the RAs really travel and represent the whole of CID in meetings with high level government officials. I remember during my second trip to Albania, we met with several of the Ministers, and I had one-on-one meetings with high level officials in the Ministry of Finance, and that’s just a unique opportunity that I couldn’t imagine having anywhere else.

What is your favorite part about working at CID’s Growth Lab?

SN: I think my favorite part is definitely the people. You have postdocs, fellows, and developers who are experts in their fields and so generous with their time. They make sure that I’m not just getting my work done, but that I’m also building skills that I can use in my future. I think it’s a place where people invest in you, and it’s not just for that deadline or for that project, but in the long run.

BZ: What I’ve most enjoyed about working at CID is how much I’ve learned while applying all of it to concrete policies in the countries we work in. I’ve learned numerous statistical methods, I’ve learned how to code in computer languages, I’ve learned how to work with the counterparts.

AG: This can be a cliché, but my favorite part about working at CID is the people and the attitude that everyone has toward the work. Everyone is willing to help when you have questions or ideas that you think are worth exploring. I can confidently say that I’ve made a lot of great friends here.

Email us at growthlab@hks.harvard.edu if you’re interested in becoming a Research Assistant at the Growth Lab and visit our Jobs page for a list of available opportunities.

This Q&A was edited for clarity and brevity.

The Case for the Albanian Investment Corporation

Re-visiting the “Sector Targeting” study: Assessing the study’s impact

Author: Neluni Tillekeratne, Sri Lanka Project Officer

Part 2: Assessing the impact of the report compiled by the “Sector Targeting Team”

Just over one and a half years ago, Sri Lanka’s Board of Investment (BOI) and Export Development Board (EDB) collaborated with the Center for International Development at Harvard University (CID) to study economic sectors for their investment and export potential.

Twenty officials from the BOI and EDB formed a “Sector Targeting Team” (or “T-Team”). The team assessed 30 sectors – all tradable activities (goods and services) of the private sector – and finally ranked their top sectors for investment and recommended strategies for promoting them. Using the Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) approach of CID’s Building State Capability program, the T-Team met weekly, working continuously over a three-month period. The resulting study represents the hard work of these dedicated government officials.

The previous post described the methodology of this study. It explored the numerous stages in which raw data across multiple indicators was analyzed, ultimately deriving a final list of subsectors with the highest potential of succeeding in the export market as products from Sri Lanka.

This post will explore if this detailed research effort went on to catalyze impact in Sri Lanka’s efforts towards export-promotion.

The team shared that despite the study being released just a short while back, it has impacted BOI across multiple tiers of strategy, action and influence. In particular, they described how the study has catalyzed impact in 8 different ways.

To document the tangible outcomes that emerged as a result of this study, I met with the lead authors (and beneficiaries) of this research initiative at the BOI: Mrs Champika Malalgoda (Executive Director, Research and Policy Advocacy), Mrs Priyanka Samaraweera (Director, Research and Policy Advocacy), and Mrs Ganga Palaketiya (Deputy Director, Research).

The team shared that despite the study being released just a short while back, it has impacted BOI across multiple tiers of strategy, action and influence. In particular, they described how the study has catalyzed impact in 8 different ways.

1. Informed strategy

Strategies derived from the BOI-EDB-Harvard study were incorporated into the BOI 2017-2020 corporate plan. The document, also known as the strategic plan, defines key targets for the institution, specifically in terms of:

- stating the BOI’s broad objectives and strategies,

- setting specific targets such as for FDI, exports, employment creation, export as a percentage of national GDP,

- identifying countries to focus on, in terms of top sources of outward investments, counties who have come to the region, and how we could approach them.

Mrs Malalgoda commended the corporate plan as the most comprehensive in the recent history of BOI, in part due to its identification of “target sectors”. The BOI focused on the top sectors recommended in the BOI-EDB-CID study, since the report predicted a high probability of returns for the investment of effort and time into these specific sectors.

2. Renewed plan of action

Given that the new corporate plan altered routine strategies of the BOI, the action plan of the institution was also revised. BOI incorporated new activities based on recommendations made by the BOI-EDB-Harvard study. The new action plan actively pursued the potential of target sectors.

The team immediately took to studying the top sectors. Mrs.Ganga was an active member of a team which acted on requirements of the action plan. Out of the identified sectors, “Electronics”, suggested “solar panels” as the highest scoring sub-sector with the highest potential of attracting a foreign investor (see figure 5).

The team identified the solar panels sector as a target sector, it was actively explored as an option by the Investor Engagement Team (I-Team). The I-Team was set up to specifically study the potential of solar panel manufacturing and other promising sectors, create pitch books, and promote the potential of the sectors to foreign investors. The team immersed themselves in practical study methods including, site visits and meeting with potential/past investors to understand the exact process through which an investor could be convinced and supported to launch a solar manufacturing initiative in SL through an FDI.

3. Reforming outdated policies

The implementation team discovered a significant number of challenges when navigating policies which governed the process of facilitating FDI and so the BOI attempted to advocate for new policies which accommodated interests of the investor and the government. Coordination with the top levels of the government helped the team secure approvals to change policies.

4. Securing investment for the “Solar panel” sector.

Investor confidence was increased as a result of such efforts. The team was ultimately responded to by one of the largest solar manufacturers in the world. Negotiations are currently underway for an FDI with this – a reward for months of dedication.

The investment was secured as a result of the team investing 6 months to study the sector. The pitch books created through the process proved to be a success.

The success of pitch books has encouraged the government to train 40 officials (from BOI and EDB) to be specialists in 10 more sectors, in hopes of finding the same success enjoyed by the I-Team in securing a much needed FDI for the country. The pitch books will be distributed to Sri Lankan Embassies and multinational companies who could potentially invest in Sri Lanka.

5. Ensuring oversight of a Coordinating Committees

A common challenge in the government structure is the existence of multiple ministries and line-agencies whose functions overlap each other. When coordinating with these agencies, 36 line agencies were identified in the process of approving all grants needed to secure an FDI for the solar sector with each line agency needing up to 12 approvals. The process is a constraint which discourages interested investors. The T-Team addressed the clear need for a coordinating committee to overlook and administer the approvals process by facilitating the formation of a committee to coordinate line agencies, in January this year.

“The study shows the need for exports and investments to be a national endeavour with multiple stakeholders in different tiers of investor promotion” – Mrs. Champika Malalgoda

6. Informing Sri Lanka’s National Export Strategy

Mrs Malalgoda shared that the prioritization of sectors suggested in the report was used to support the formulation of the recently launched National Export Strategy (NES) of the EDB. The integration of research into initiatives across the government is an example of knowledge sharing across institutions.

7. Facilitating the launch of new industrial zones in SL for the first time in 15 years

The BOI even addressed crucial bottlenecks in FDI promotion, especially the availability of land for industrial zones. Mrs Priyanka Samaraweera was part of the land team which set out to understand the issues around the lack of suitable land for new manufacturing plants. The following success story of the land team was shared as one of the most rewarding results of the T-Team report.

“Access to land for new ventures is considered a bottleneck in the process of securing investor confidence. More than 80% of land in the country is owned by the government, and the government’s export processing zones are for the most part fully occupied; as a result, interested investors often turn away due to the lack of suitable industrial locations. To further understand the land constraints, an L-Team (land team), engaged in a research exercise. They compiled a comprehensive database on potential plots of land which could be used as Industrial zones. The team conducted a land analysis and matched the available facilities in vacant plots of land, to the specifications required by an investor of a targeted sector, with the preliminary analysis assessing over 80 plots of land.

It was interesting to note that when ideal requirements for an industrial zone were assessed, the newly identified lands offered conditions comparable to the BOI’s existing zones such as in Katunayke and Biyagama. Finally, 25 lands were identified as potential industrial zones” – Mrs. Priyanka Samaraweera

Three lands have now been identified by the government to be developed into industrial zones, including Mawathagama, Bingiriya and Milleniya, an initiative by the government for the first time in over 15 years. This is one of the most impactful results of the study. This progress is a direct result of the BOI-CID study. Coordination toward establishing a new industrial zone improved through the identification of new sectors through the study.

Will this impact continue to multiply?

Mrs. Malalgoda believes the study will go on to inform a policy framework which will support new zones. The policy will be designed to maximize the output and facilitate efficient administration of each zone.

“The final outcome is a rich resource in which any potential investor, researcher, or another interested party can obtain over sixty data points on any sector, as well as aggregated index scores for six major factors. We also hope that by providing access to this research, it may serve as a model for other economic development institutions as well.” – Mrs. Champika Malalgoda

A number of institutions supported the hard-working team at the BOI including the Department of Census and Statics and the Department of Customs who provided in-depth, high-quality data to support the research initiative. The report informed many stakeholders who work towards a common goal of reviving the Sri Lankan economy. We look forward to visiting this team again in a year or so, to hear more stories of the impact of the T-Team report.

“I have realized why by observing this team in Sri Lanka: they are more committed to the work than any outside consultant I have ever seen (because it is their country, and the result of today’s diversification efforts will have a huge impact on the team members’ children) and bring vital contextual know- how to the job better than any outside consultant” – Matt Andrews, Senior Lecturer in International Development, Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Associate, Harvard Center for International Development

Investments are considered a main source of sustainable growth, yet developing countries often lack the management capacity and knowhow to develop their assets. This is where structures such as investment agencies, granted that they are set up properly, can be instrumental in realizing investment potential. Over the summer, Damian worked with the government to lay the groundwork for the development of an

Investments are considered a main source of sustainable growth, yet developing countries often lack the management capacity and knowhow to develop their assets. This is where structures such as investment agencies, granted that they are set up properly, can be instrumental in realizing investment potential. Over the summer, Damian worked with the government to lay the groundwork for the development of an  Setting up systems for continuity is important and helps address many of the issues associated with short-term engagement. To accommodate the academic schedule, the Growth Lab internship lasts for eight to ten weeks and create a wide range of challenges including condensed time to get to know systems and stakeholders and limited influence on policies after the internships end. In this context, good policy in practice means laying the groundwork for environments that are conducive to implementation of policies and creating systems and records to ensure that knowledge is not lost once engagement ends. This is true not only for internships and short-term engagements but for government offices as well.

Setting up systems for continuity is important and helps address many of the issues associated with short-term engagement. To accommodate the academic schedule, the Growth Lab internship lasts for eight to ten weeks and create a wide range of challenges including condensed time to get to know systems and stakeholders and limited influence on policies after the internships end. In this context, good policy in practice means laying the groundwork for environments that are conducive to implementation of policies and creating systems and records to ensure that knowledge is not lost once engagement ends. This is true not only for internships and short-term engagements but for government offices as well.