By Eric Protzer

Cheyenne is the capital of Wyoming, with a population of approximately 65,000. The state of Wyoming as a whole has faced a durable shortage of housing, and like any supply shortage, this has led to inflated prices. Yet in recent years, Cheyenne has enacted several important housing reforms that allow the market to more flexibly create the supply that people demand. This has led to a surge in housing permits and construction, which is set to ease the underlying market pressures behind housing unaffordability.

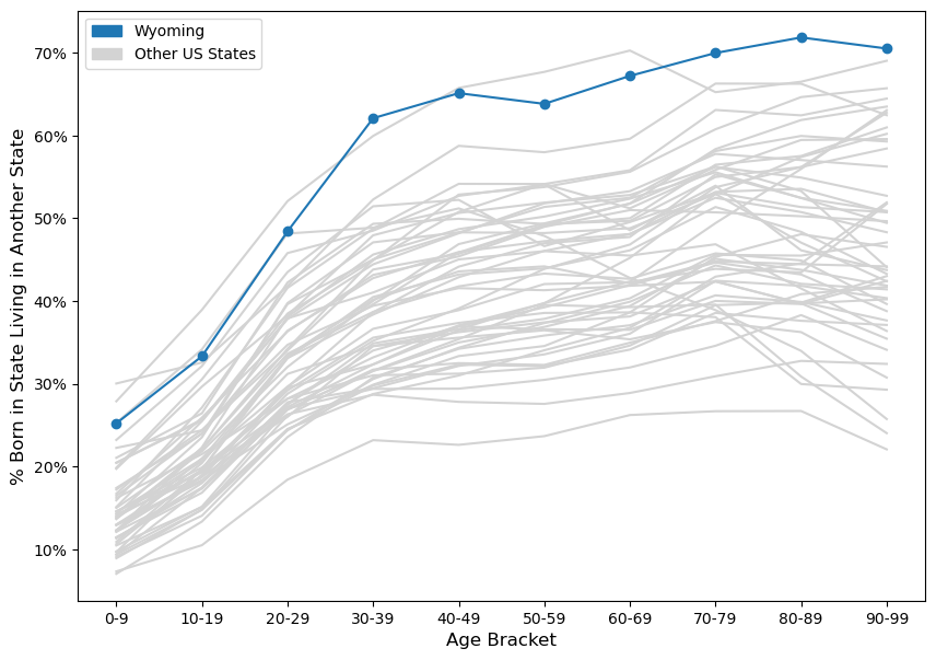

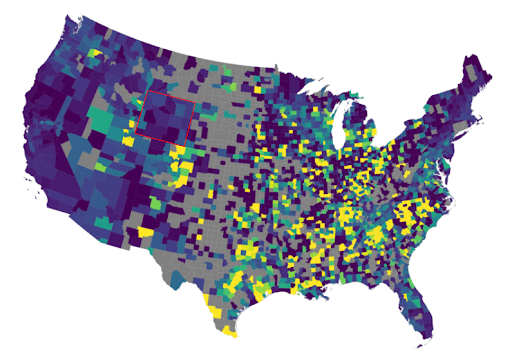

Figure 1 exhibits a map of housing supply elasticity in the US, with Wyoming highlighted. Elasticity is a key metric that economists use to determine how responsive supply is to demand. In this case, it measures the ratio of supply to price growth during periods of sustained local price growth. In dark areas of the map (including Wyoming), elasticity is low, and thus, housing supply doesn’t increase very much at all when prices increase. In brighter areas of the map, conversely, supply increases more substantially when prices rise. This is crucial because increased supply helps to mitigate price pressures.

Figure 1. Map of US Housing Elasticity, with Wyoming Highlighted

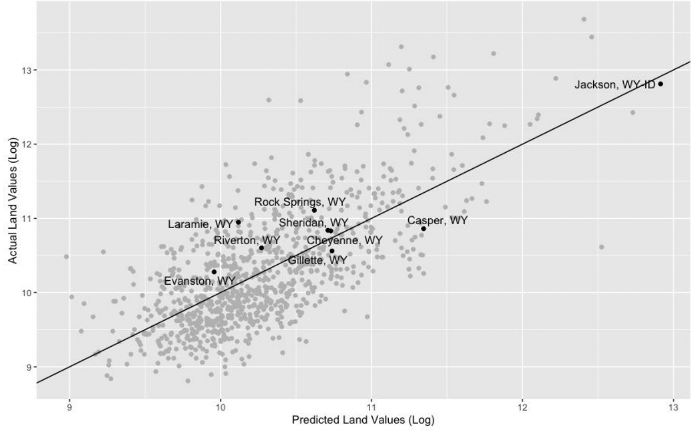

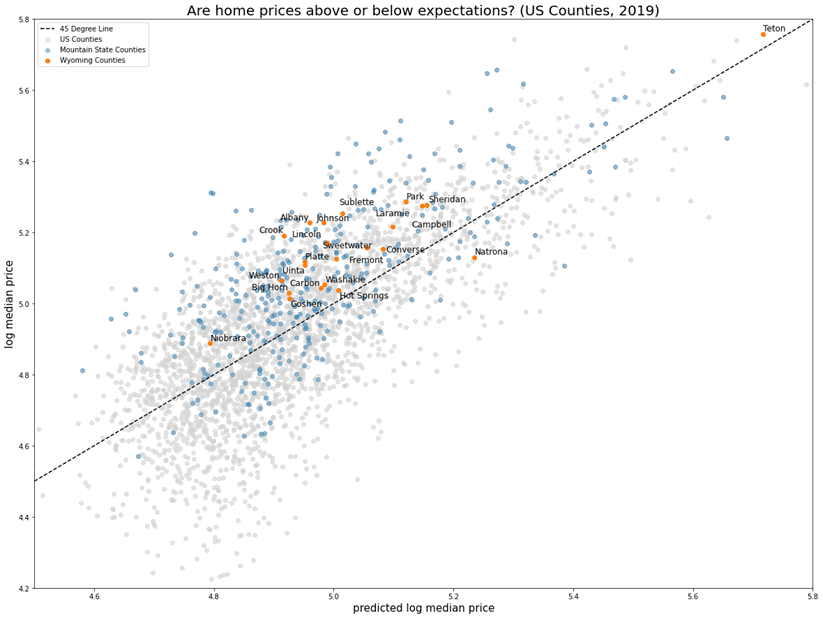

Figure 2 shows that Wyoming’s home prices in 2019 were generally above expectations given economic fundamentals such as population, income, and remoteness. This is an unsurprising conclusion: supply shortages lead to high prices.

Figure 2. Actual vs. Statistically-Expected Home Prices by US County

Many economists would argue that the leading cause of housing supply shortages across important parts of the US is the presence of high regulatory barriers to housing development. The costs of financing, labor, and materials are not terribly different between California and Texas, for example, but Texas builds a lot more housing (see Figure 1) because of a much more free-market regulatory environment.

More specifically, American towns with housing shortages often have strict zoning codes that make it very difficult to develop dense housing, such as starter homes with small yards that are suitable for young families, or apartment buildings suitable for young adults, at prices the average person can afford. Such restrictions can include maximum building heights, minimum lot sizes, minimum setbacks, minimum parking space requirements, zoning that disallows multi-family housing, and more. Lengthy approval processes, which can require multiple public hearings and town council votes, further compound costs by creating delays and uncertainty.

Examples of economic research linking housing regulatory restrictions to unaffordability include:

- Zabel and Dalton (2011) find that minimum lot sizes in Massachusetts increase housing prices by 20% – 40%.

- Hilber and Vermeulen (2016) find that the South East of England would have had 25% lower housing prices if it had followed the lower regulatory burden of the North East.

- Molloy et al. (2022) find that a one standard deviation increase in regulatory supply constraints leads to 10% faster house price growth.

Intuitively, these regulations are influential because they force renters and homebuyers to pay for things they don’t want. In turn, this dramatically reduces supply and increases the price of housing. For example, some US towns impose large minimum lot sizes. These require large yards for all homes, which can look nice, but are expensive due to the cost of land. Young families often prefer more affordable homes with significantly smaller yards, yet regulations prevent the market from building the type of housing supply that is in fact demanded.

The alternative approach is to let the market decide these issues by not regulating them. For example, France has not had any minimum lot sizes nationwide since 2013.

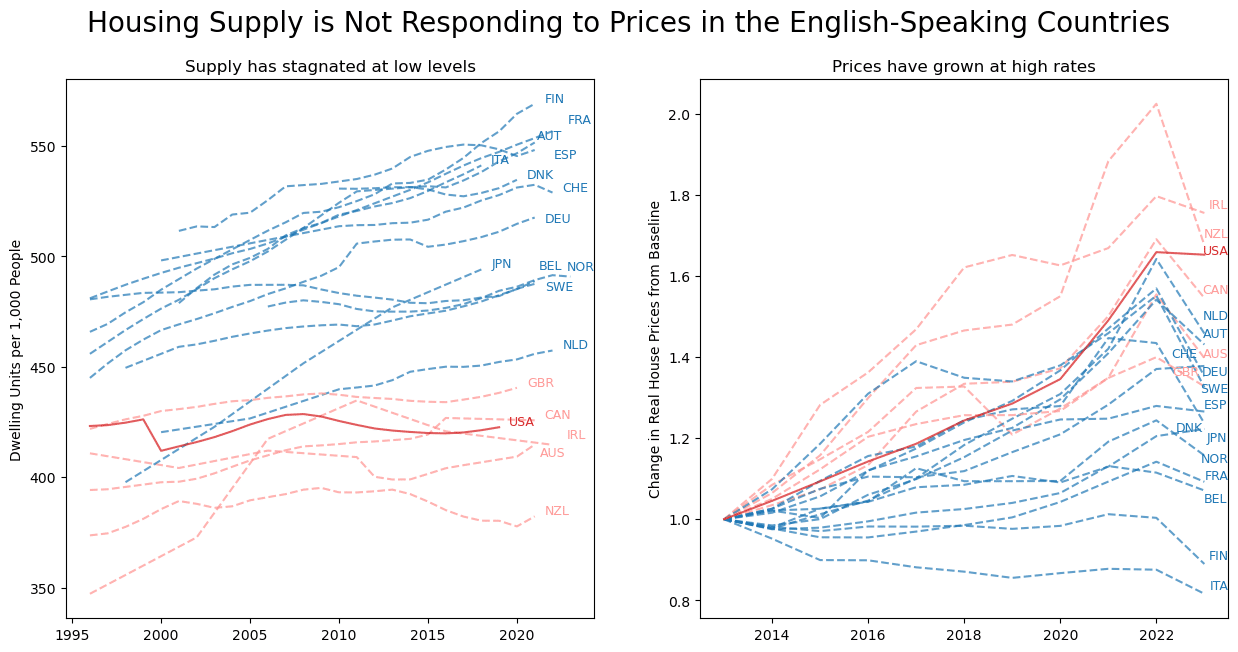

The regulatory problem can, in fact, be so severe that it is evident at the national level. Figure 3 shows that English-speaking countries have stagnated at low levels of housing supply per capita, while the growth of their housing prices has far exceeded that of other high-income countries. Again, the costs of major inputs such as financing, labor, and materials are not enormously different across high-income countries. But English-speaking countries have much higher regulatory barriers to dense housing development, which stem from their common-law legal institutions.

Figure 3. Housing Supply and Prices among High-Income Countries

In light of these dynamics, it is highly notable that Cheyenne has significantly reduced regulatory barriers to new housing supply. Key reforms since 2020 include:

- The creation of “urban loft” uses in commercially-zoned areas of town, which allow the development of apartments.

- Allowed multi-family residential and mixed-use buildings in the primary commercial zone district (Community Business).

- The maximum lot coverage ratio was increased to 80% for several uses, including standard and large lot size multi-family buildings. This allows a larger share of the land area to be used for the building footprint and parking, as opposed to being left as empty space or landscaping. In turn, this effectively reduces the amount of extra unused land and increased perimeter infrastructure (streets, sidewalks, utilities, etc.) that each renter must pay for, which considerably improves affordability.

- Removed required lot area per multi-family unit, which was previously 1,600 sq ft per unit or 1,000 sq ft per unit if above three stories. This similarly reduces the amount of unused land that each renter must pay for, which dramatically improves affordability. For example, a five-story, 50-unit apartment with a building footprint of roughly 10,000 square feet would previously have had to pay for nearly an extra acre of unused land, which in central parts of town can become very expensive.

- Removed all residential minimum lot sizes. This also helps save on the costs of unused land, which is crucial for both multi-family developments and starter homes with small yards.

- Created an urban use overlay that allows for building heights up to 65 feet, lot coverage ratios from 90% – 100%, no minimum setbacks (except on one particular street), and removed minimum parking requirements. This enables especially dense development west of Cheyenne’s downtown, which allows people to live within walking distance to work and provides enhanced foot traffic for local businesses.

- Reduced minimum parking space requirements from 1.5 spaces to 1 space for studio and one-unit multi-family dwelling units.

- Removed luxury material requirements for multifamily building facades and display window requirements for multi-family dwellings.

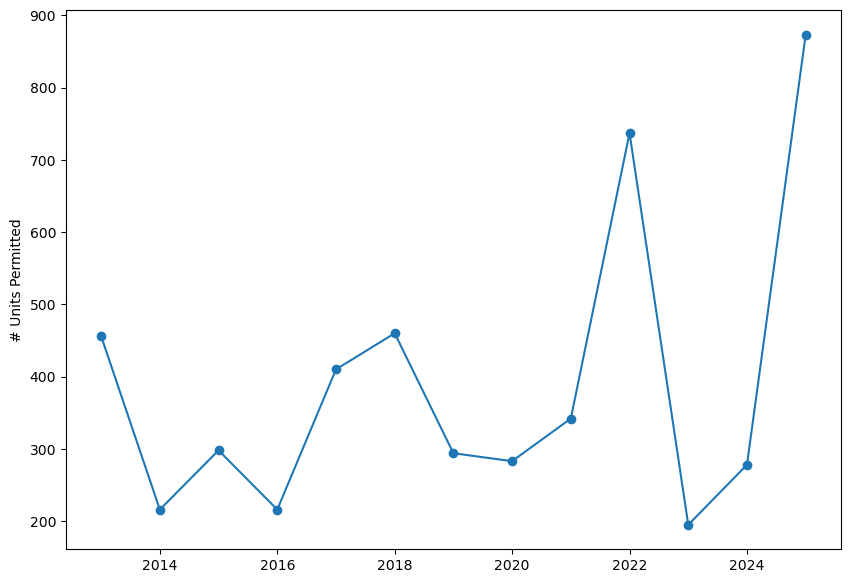

Since this reform effort kicked off circa 2020, Cheyenne has enjoyed bumper years of enhanced housing supply growth (Figure 4). The number of units permitted in 2025 is approximately 2.6 times the annual average from 2013-2019.

Figure 4. Number of Housing Units Permitted Annually in Cheyenne

As matters stand, Cheyenne is especially competitive with nearby towns on lot area requirements (Table 1). Further reform could be enacted in some instances, for example, to further reduce certain multi-family parking space requirements.

Table 1. Housing Regulations in Cheyenne vs. Nearby Towns

| Cheyenne, WY | Laramie, WY | Casper, WY | Fort Collins, CO | |

| Range of minimum lot sizes for residential zones1 | None | 2,000 to 8,000 sq ft | 4,000 to 9,000 sq ft | 0 to 2.29 acres |

| Largest required lot area per multi-family unit | None | 1,250 sq ft per unit | 2,420 sq ft per unit | 3,630 sq ft per unit |

| Largest minimum setback | 50 ft | 60 ft | 18 ft | 80 ft |

| Smallest maximum multi-family building height | 3-4 stories2 | 40 ft | 40 ft | 28 ft |

| Largest minimum parking space requirement per multi-family unit | 1.5 spaces per unit | 1.5 spaces per unit | 1 space per unit | None |

On the whole, Cheyenne has made impressive efforts to reduce regulatory barriers to housing and is seeing a surge of housing supply as a result. Other small towns around America should learn from this example and reduce their regulatory barriers to dense housing accordingly.

1 Excluding zones for agriculture or manufactured homes

2 Some usages allow garden-level units, which may not count as a story depending on interpretation